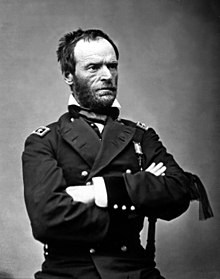

William Tecumseh Sherman (February 8, 1820 – February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–65), for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the scorched earth policies he implemented in conducting total war against the Confederate States.[2]

William Tecumseh Sherman (February 8, 1820 – February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War (1861–65), for which he received recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy as well as criticism for the harshness of the scorched earth policies he implemented in conducting total war against the Confederate States.[2]

Sherman was born into a prominent political family. He graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1840 and was stationed in California. He married Ellen Ewing Sherman and together they raised eight children. Sherman’s wife and children were all devout Catholics, while Sherman was originally a member of the faith but later left it. In 1859, he gained a position as superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning & Military Academy. Living in the South, Sherman grew to respect Southern culture and sympathize with the practice of Southern slavery, although he opposed secession.

Sherman began his Civil War career serving with distinction in the First Battle of Bull Run before being transferred to the Western Theater. He served in Kentucky in 1861, where he acted overly paranoid, exaggerating the presence of spies in the region and providing what seemed to be alarmingly high estimates of the number of troops needed to pacify Kentucky. He was granted leave, and fell into depression. Sherman returned to serve under General Ulysses S. Grant in the winter of 1862 during the battles of forts Henry and Donelson. Before the Battle of Shiloh, Sherman commanded a division. Failing to make proper preparations for a Confederate offensive, his men were surprised and overrun. He later rallied his division and helped drive the Confederates back. Sherman later served in the Siege of Corinth and commanded the XV Corps during the Vicksburg Campaign, which led to the fall of the critical Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg on the Mississippi River. After Grant was promoted to command of all Western armies, Sherman took over the Army of the Tennessee and led it during the Chattanooga Campaign, which culminated with the routing of the Confederate armies in the state of Tennessee.

In 1864, Sherman succeeded Grant as the Union commander in the western theater of the war. He proceeded to lead his troops to the capture of the city of Atlanta, a military success that contributed to the re-election of Abraham Lincoln. Sherman’s subsequent march through Georgia and the Carolinas further undermined the Confederacy’s ability to continue fighting by destroying large amounts of supplies and demoralizing the Southern people. The tactics that he used during this march, though effective, remain a subject of controversy. He accepted the surrender of all the Confederate armies in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida in April 1865, after having been present at most major military engagements in the West. When Grant assumed the U.S. presidency in 1869, Sherman succeeded him as Commanding General of the Army, in which capacity he served from 1869 until 1883. As such, he was responsible for the U.S. Army’s engagement in the Indian Wars over the next 15 years. Sherman advocated total war against hostile Indians to force them back onto their reservations. He was skeptical of the Reconstruction era policies of the federal government in the South. Sherman steadfastly refused to be drawn into politics and in 1875 published his Memoirs, one of the best-known first-hand accounts of the Civil War. British military historian B. H. Liddell Hart declared that Sherman was “the first modern general.”[3]

Chattanooga

After the surrender of Vicksburg to the Union forces under Grant on July 4, 1863, Sherman was given the rank of brigadier general in the regular army, in addition to his rank as a major general of volunteers. Sherman’s family came from Ohio to visit his camp near Vicksburg; his nine-year-old son, Willie, the Little Sergeant, died from typhoid fever contracted during the trip.[62]

Command in the West was unified under Grant (Military Division of the Mississippi), and Sherman succeeded Grant in command of the Army of the Tennessee. Following the defeat of the Army of the Cumberland at the Battle of Chickamauga by Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, the army was besieged in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Sherman’s troops were sent to relieve them. While traveling to Chattanooga, Sherman departed Memphis on a train that arrived at the Battle of Collierville, Tennessee, while the Union garrison there was under attack on October 11, 1863. General Sherman took command of the 550 men and successfully defended against an attack of 3,500 Confederate cavalry.

During the Chattanooga Campaign in November, under Grant’s overall command, Sherman quickly took his assigned target of Billy Goat Hill at the north end of Missionary Ridge, only to discover that it was not part of the ridge at all, but rather a detached spur separated from the main spine by a rock-strewn ravine. When he attempted to attack the main spine at Tunnel Hill, his troops were repeatedly repulsed by Patrick Cleburne’s heavy division, the best unit in Bragg’s army. Sherman’s efforts were assisted by George Henry Thomas’s army’s successful assault on the center of the Confederate line, a movement originally intended as a diversion.[63] Subsequently, Sherman led a column to relieve Union forces under Ambrose Burnside thought to be in peril at Knoxville. In February 1864, he led an expedition to Meridian, Mississippi, to disrupt Confederate infrastructure.[64]

Atlanta

Despite this mixed record, Sherman enjoyed Grant’s confidence and friendship. When Lincoln called Grant east in the spring of 1864 to take command of all the Union armies, Grant appointed Sherman (by then known to his soldiers as “Uncle Billy”) to succeed him as head of the Military Division of the Mississippi, which entailed command of Union troops in the Western Theater of the war. As Grant took overall command of the armies of the United States, Sherman wrote to him outlining his strategy to bring the war to an end concluding that “if you can whip Lee and I can march to the Atlantic I think ol’ Uncle Abe will give us twenty days leave to see the young folks.”[65]

Sherman proceeded to invade the state of Georgia with three armies: the 60,000-strong Army of the Cumberland under George Henry Thomas, the 25,000-strong Army of the Tennessee under James B. McPherson, and the 13,000-strong Army of the Ohio under John M. Schofield.[66] He fought a lengthy campaign of maneuver through mountainous terrain against Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee, attempting a direct assault only at the disastrous Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. In July, the cautious Johnston was replaced by the more aggressive John Bell Hood, who played to Sherman’s strength by challenging him to direct battles on open ground. Meanwhile, in August, Sherman “learned that I had been commissioned a major-general in the regular army, which was unexpected, and not desired until successful in the capture of Atlanta.”[67]

Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign concluded successfully on September 2, 1864, with the capture of the city, which Hood had been forced to abandon. This success made Sherman a household name and helped ensure Lincoln’s presidential re-election in November. In August, the Democratic Party had nominated as its candidate George B. McClellan, the popular former Union army commander, and it had seemed likely that Lincoln would lose to McClellan. Lincoln’s defeat could well have meant the victory of the Confederacy, as the Democratic Party platform called for peace negotiations based on the acknowledgment of the Confederacy’s independence. Thus the capture of Atlanta, coming when it did, may have been Sherman’s greatest contribution to the Union cause.[68]

After ordering almost all civilians to leave the city in September, Sherman gave instructions that all military and government buildings in Atlanta be burned, although many private homes and shops were burned as well.[69] This was to set a precedent for future behavior by his armies.

March to the Sea

Main article: Sherman’s March to the Sea

During September and October, Sherman and Hood played cat-and-mouse in north Georgia (and Alabama) as Hood threatened Sherman’s communications to the north. Eventually, Sherman won approval from his superiors for a plan to cut loose from his communications and march south, having advised Grant that he could “make Georgia howl”.[70] This created the threat that Hood would move north into Tennessee. Trivializing that threat, Sherman reportedly said that he would “give [Hood] his rations” to go in that direction as “my business is down south”.[71] However, Sherman left forces under Maj. Gens. George H. Thomas and John M. Schofield to deal with Hood; their forces eventually smashed Hood’s army in the battles of Franklin (November 30) and Nashville (December 15–16).[72] Meanwhile, after the November elections, Sherman began a march with 62,000 men to the port of Savannah, Georgia, living off the land and causing, by his own estimate, more than $100 million in property damage.[73] Sherman called this harsh tactic of material war “hard war,” often seen as a species of total war.[74] At the end of this campaign, known as Sherman’s March to the Sea, his troops captured Savannah on December 21, 1864.[75] Sherman then dispatched a famous message to Lincoln, offering him the city as a Christmas present.[76]

Sherman’s success in Georgia received ample coverage in the Northern press at a time when Grant seemed to be making little progress in his fight against Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. A bill was introduced in Congress to promote Sherman to Grant’s rank of lieutenant general, probably with a view towards having him replace Grant as commander of the Union Army. Sherman wrote both to his brother, Senator John Sherman, and to General Grant vehemently repudiating any such promotion.[77] According to a war-time account,[78] it was around this time that Sherman made his memorable declaration of loyalty to Grant:

General Grant is a great general. I know him well. He stood by me when I was crazy, and I stood by him when he was drunk; and now, sir, we stand by each other always.

While in Savannah, Sherman learned from a newspaper that his infant son Charles Celestine had died during the Savannah Campaign; the general had never seen the child.[79]

Final campaigns in the Carolinas

Grant then ordered Sherman to embark his army on steamers and join the Union forces confronting Lee in Virginia, but Sherman instead persuaded Grant to allow him to march north through the Carolinas, destroying everything of military value along the way, as he had done in Georgia. He was particularly interested in targeting South Carolina, the first state to secede from the Union, because of the effect that it would have on Southern morale.[80] His army proceeded north through South Carolina against light resistance from the troops of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. Upon hearing that Sherman’s men were advancing on corduroy roads through the Salkehatchie swamps at a rate of a dozen miles per day, Johnston “made up his mind that there had been no such army in existence since the days of Julius Caesar.”[81]

Sherman captured the state capital of Columbia, South Carolina, on February 17, 1865. Fires began that night and by next morning most of the central city was destroyed. The burning of Columbia has engendered controversy ever since, with some claiming the fires were accidental, others a deliberate act of vengeance, and still others that the retreating Confederates burned bales of cotton on their way out of town.[82]

Local Native American Lumbee guides helped Sherman’s army cross the Lumber River, which was flooded by torrential rains, into North Carolina. According to Sherman, the trek across the Lumber River, and through the swamps, pocosins, and creeks of Robeson County was “the damnedest marching I ever saw.”[83] Thereafter, his troops did little damage to the civilian infrastructure, as North Carolina, unlike its southern neighbor, was regarded by his men as a reluctant Confederate state, having been the second from last state to secede from the Union, before Tennessee. Sherman’s final significant military engagement was a victory over Johnston’s troops at the Battle of Bentonville, March 19–21. He soon rendezvoused at Goldsborough, North Carolina, with Union troops awaiting him there after the capture of Fort Fisher and Wilmington.

In late March, Sherman briefly left his forces and traveled to City Point, Virginia to consult with Grant. Lincoln happened to be at City Point at the same time, allowing the only three-way meetings of Lincoln, Grant, and Sherman during the war.[84]

Confederate surrender

Following Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House and the assassination of President Lincoln, Sherman met with Johnston in mid-April at Bennett Place in Durham, North Carolina, to negotiate a Confederate surrender. At the insistence of Johnston and of Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Sherman conditionally agreed to generous terms that dealt with both political and military issues. Sherman thought that those terms were consistent with the views Lincoln had expressed at City Point, but the general had not been given the authority, by General Grant, the newly installed President Andrew Johnson, or the Cabinet, to offer those terms.

The government in Washington, D.C., refused to approve Sherman’s terms and the Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, denounced Sherman publicly, precipitating a long-lasting feud between the two men. Confusion over this issue lasted until April 26, 1865, when Johnston, ignoring instructions from President Davis, agreed to purely military terms and formally surrendered his army and all the Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida, in what was the largest single capitulation of the war.[85] Sherman proceeded with 60,000 of his troops to Washington, D.C., where they marched in the Grand Review of the Armies, on May 24, 1865, and were then disbanded. Having become the second most important general in the Union army, he thus had come full circle to the city where he started his war-time service as colonel of a non-existent infantry regiment.

Strategies

Sherman’s record as a tactician was mixed, and his military legacy rests primarily on his command of logistics and on his brilliance as a strategist. The influential 20th-century British military historian and theorist B. H. Liddell Hart ranked Sherman as one of the most important strategists in the annals of war, along with Scipio Africanus, Belisarius, Napoleon Bonaparte, T. E. Lawrence, and Erwin Rommel. Liddell Hart credited Sherman with mastery of maneuver warfare (also known as the “indirect approach”), as demonstrated by his series of turning movements against Johnston during the Atlanta Campaign. Liddell Hart also stated that study of Sherman’s campaigns had contributed significantly to his own “theory of strategy and tactics in mechanized warfare”, which had in turn influenced Heinz Guderian’s doctrine of Blitzkrieg and Rommel’s use of tanks during the Second World War.[95] Another World War II-era student of Liddell Hart’s writings about Sherman was George S. Patton, who “‘spent a long vacation studying Sherman’s campaigns on the ground in Georgia and the Carolinas, with the aid of [Liddell Hart’s] book'” and later “‘carried out his [bold] plans, in super-Sherman style'”.[96]

Sherman’s greatest contribution to the war, the strategy of total warfare—endorsed by General Grant and President Lincoln—has been the subject of controversy. Sherman himself downplayed his role in conducting total war, often saying that he was simply carrying out orders as best he could in order to fulfill his part of Grant’s master plan for ending the war.

Total warfare

See also: Sherman’s March to the Sea

Like Grant, Sherman was convinced that the Confederacy’s strategic, economic, and psychological ability to wage further war needed to be definitively crushed if the fighting were to end. Therefore, he believed that the North had to conduct its campaign as a war of conquest and employ scorched earth tactics to break the backbone of the rebellion. He called this strategy “hard war”.

Sherman’s advance through Georgia and South Carolina was characterized by widespread destruction of civilian supplies and infrastructure. Although looting was officially forbidden, historians disagree on how well this regulation was enforced.[97] Union soldiers who foraged from Southern homes became known as bummers. The speed and efficiency of the destruction by Sherman’s army was remarkable. The practice of heating rails and bending them around trees, leaving behind what came to be known as “Sherman’s neckties,” made repairs difficult. Accusations that civilians were targeted and war crimes were committed on the march have made Sherman a controversial figure to this day, particularly in the American South.

The damage done by Sherman was almost entirely limited to the destruction of property. Though exact figures are not available, the loss of civilian life appears to have been very small.[98] Consuming supplies, wrecking infrastructure, and undermining morale were Sherman’s stated goals, and several of his Southern contemporaries noted this and commented on it. For instance, Alabama-born Major Henry Hitchcock, who served in Sherman’s staff, declared that “it is a terrible thing to consume and destroy the sustenance of thousands of people,” but if the scorched earth strategy served “to paralyze their husbands and fathers who are fighting … it is mercy in the end”.[99]

The severity of the destructive acts by Union troops was significantly greater in South Carolina than in Georgia or North Carolina. This appears to have been a consequence of the animosity among both Union soldiers and officers to the state that they regarded as the “cockpit of secession”.[100] One of the most serious accusations against Sherman was that he allowed his troops to burn the city of Columbia. In 1867, Gen. O. O. Howard, commander of Sherman’s 15th Corps, reportedly said, “It is useless to deny that our troops burnt Columbia, for I saw them in the act.”[101] However, Sherman himself stated that “[i]f I had made up my mind to burn Columbia I would have burnt it with no more feeling than I would a common prairie dog village; but I did not do it …”[102] Sherman’s official report on the burning placed the blame on Confederate Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton III, who Sherman said had ordered the burning of cotton in the streets. In his memoirs, Sherman said, “In my official report of this conflagration I distinctly charged it to General Wade Hampton, and confess I did so pointedly to shake the faith of his people in him, for he was in my opinion a braggart and professed to be the special champion of South Carolina.”[103] Historian James M. McPherson has concluded that:

The fullest and most dispassionate study of this controversy blames all parties in varying proportions—including the Confederate authorities for the disorder that characterized the evacuation of Columbia, leaving thousands of cotton bales on the streets (some of them burning) and huge quantities of liquor undestroyed … Sherman did not deliberately burn Columbia; a majority of Union soldiers, including the general himself, worked through the night to put out the fires.[104]

In this general connection, it is also noteworthy that Sherman and his subordinates (particularly John A. Logan) took steps to protect Raleigh, North Carolina, from acts of revenge after the assassination of President Lincoln.[105]

Content retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Tecumseh_Sherman.

Images

[URIS id=1211]Videos

[relatedYouTubeVideos max="1"]