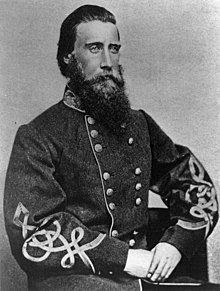

John Bell Hood (June 1[2] or June 29,[3] 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Hood had a reputation for bravery and aggressiveness that sometimes bordered on recklessness. Arguably one of the best brigade and division commanders in the CSA, Hood gradually became increasingly ineffective as he was promoted to lead larger, independent commands late in the war; his career and reputation were marred by his decisive defeats leading an army in the Atlanta Campaign and the Franklin–Nashville Campaign.

John Bell Hood (June 1[2] or June 29,[3] 1831 – August 30, 1879) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War. Hood had a reputation for bravery and aggressiveness that sometimes bordered on recklessness. Arguably one of the best brigade and division commanders in the CSA, Hood gradually became increasingly ineffective as he was promoted to lead larger, independent commands late in the war; his career and reputation were marred by his decisive defeats leading an army in the Atlanta Campaign and the Franklin–Nashville Campaign.

Hood’s education at the United States Military Academy led to a career as a junior officer in both the infantry and cavalry of the antebellum U.S. Army in California and Texas. At the start of the Civil War, he offered his services to his adopted state of Texas. He achieved his reputation for aggressive leadership as a brigade commander in the army of Robert E. Lee during the Seven Days Battles in 1862, after which he was promoted to division command. He led a division under James Longstreet in the campaigns of 1862–63. At the Battle of Gettysburg, he was severely wounded, rendering his left arm useless for the rest of his life. Transferred with many of Longstreet’s troops to the Western Theater, Hood led a massive assault into a gap in the Union line at the Battle of Chickamauga, but was wounded again, requiring the amputation of his right leg.

Hood returned to field service during the Atlanta Campaign of 1864, and at the age of 33 was promoted to temporary full general and command of the Army of Tennessee at the outskirts of Atlanta, making him the youngest soldier on either side of the war to be given command of an army. There, he dissipated his army in a series of bold, calculated, but unfortunate assaults, and was forced to evacuate the besieged city. Leading his men through Alabama and into Tennessee, his army was severely damaged in a massive frontal assault at the Battle of Franklin and he was decisively defeated at the Battle of Nashville by his former West Point instructor, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, after which he was relieved of command.

After the war, Hood moved to Louisiana and worked as a cotton broker and in the insurance business. His business was ruined by a yellow fever epidemic in New Orleans during the winter of 1878–79 and he succumbed to the disease himself, dying just days after his wife and oldest child, leaving ten destitute orphans.

Atlanta Campaign and the Army of Tennessee

In the spring of 1864, the Confederate Army of Tennessee, under Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, was engaged in a campaign of maneuver against William T. Sherman, who was driving from Chattanooga toward Atlanta. Despite his two damaged limbs, Hood performed well in the field, riding as much as 20 miles a day without apparent difficulty, strapped to his horse with his artificial leg hanging stiffly, and an orderly following closely behind with crutches. The leg, made of cork, was donated (along with a couple of spares) by members of his Texas Brigade, who had collected $3,100 in a single day for that purpose; it had been imported from Europe through the Union blockade.[36] On May 12, Hood was baptized by Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk, the former Episcopal Bishop of Louisiana. Colonel Walter H. Rodgers, a witness to the baptism, stated that Hood “looked happy and as though a great burden had been lifted.”[37]

During the Atlanta Campaign, Hood urged the normally cautious Johnston to act aggressively, but Johnston usually reacted to flanking maneuvers by Sherman with timely withdrawals, rather similar to his strategy in the Peninsula Campaign. One attempt by Johnston to act decisively in the offensive, during the Battle of Cassville, ironically was foiled by Hood, who had been ordered to attack the flank of one column of Sherman’s army, but instead pulled back and entrenched when confronted by the unexpected arrival of a small detachment of that column.[38]

The Army of Tennessee continued withdrawing until it had crossed the last major water barrier before Atlanta, the Chattahoochee River. During this time, Hood had been sending the government in Richmond letters very critical of Johnston’s conduct, bypassing official communication channels. The issue came to a head when Gen. Braxton Bragg was ordered by President Davis to travel to Atlanta to personally interview Johnston. After meeting with Johnston, he interviewed Hood and another subordinate, Joseph Wheeler, who told him that they had repeatedly urged Johnston to attack. Hood presented a letter that branded Johnston as being both ineffective and weak-willed. He told Bragg, “I have, General, so often urged that we should force the enemy to give us battle as to almost be regarded reckless by the officers high in rank in this army [meaning Johnston and senior corps commander William J. Hardee], since their views have been so directly opposite.” Johnston’s biographer, Craig L. Symonds, judges that Hood’s letter “stepped over the line from unprofessional to outright subversive.” Civil War historian Steven E. Woodworth wrote that Hood was “letting his ambition get the better of his honesty” because “the truth was that Hood, more often than Hardee, had counseled Johnston to retreat.”[39] However, Hood was not alone in his criticism of Johnston’s timidity. In William Hardee’s June 22, 1864, letter to General Bragg, he stated, “If the present system continues we may find ourselves at Atlanta before a serious battle is fought.” Other generals in the Army agreed with that assessment.[40]

On July 17, 1864, Jefferson Davis relieved Johnston. He considered replacing him with the more senior Hardee, but Bragg strongly recommended Hood. Bragg had not only been impressed by his interview with Hood, but he retained lingering resentments against Hardee from bitter disagreements in previous campaigns. Hood was promoted to the temporary rank of full general on July 18, and given command of the army just outside the gates of Atlanta. (Hood’s temporary appointment as a full general was never confirmed by the Senate. His commission as a lieutenant general resumed on January 23, 1865.[12]) At 33, Hood was the youngest man on either side to be given command of an army. Robert E. Lee gave an ambiguous reply to Davis’s request for his opinion about the promotion, calling Hood “a bold fighter, very industrious on the battlefield, careless off,” but he could not say whether Hood possessed all of the qualities necessary to command an army in the field.[41] Lee also stated in the same letter to Jefferson Davis that he had a high opinion of Hood’s gallantry, earnestness, and zeal.[42]

The change of command in the Army of Tennessee did not go unnoticed by Sherman. His subordinates, James B. McPherson and John M. Schofield, shared their knowledge of Hood from their time together at West Point. Upon learning of his new adversary’s perceived reckless and gambling tendencies, Sherman planned to use that to his advantage.[43]

Hood conducted the remainder of the Atlanta Campaign with the strong aggressive actions for which he had become famous. He launched four major attacks that summer in an attempt to break Sherman’s siege of Atlanta, starting almost immediately with an attack along Peachtree Creek. After hearing that McPherson was mortally wounded in the Battle of Atlanta, Hood deeply regretted his loss.[44] All of the offensives failed, particularly at the Battle of Ezra Church, with significant Confederate casualties. Finally, on September 2, 1864, Hood evacuated the city of Atlanta, burning as many military supplies and installations as possible.[45]

Content retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Bell_Hood.

Images

[URIS id=1289]