Guerrilla warfare in Georgia during the Civil War (1861-65) often took place in sparsely populated regions where Unionist or anti-Confederate sentiment created divisions among the civilian population. In many cases Unionist and Confederate neighbors clashed for control of their communities. In other instances guerrillas operated against major field armies. Confederate guerrilla activities affected the policies of Union general William T. Sherman, pushing him to adopt harsh retaliatory measures to protect his railroad supply lines as he moved through Georgia in 1864. In the final stages of the Civil War, guerrilla activities became an acute problem for areas in which civil authority had broken down. Irregular bands terrorized and plundered farms and towns, killing or wounding large numbers of people.

Guerrilla warfare in Georgia during the Civil War (1861-65) often took place in sparsely populated regions where Unionist or anti-Confederate sentiment created divisions among the civilian population. In many cases Unionist and Confederate neighbors clashed for control of their communities. In other instances guerrillas operated against major field armies. Confederate guerrilla activities affected the policies of Union general William T. Sherman, pushing him to adopt harsh retaliatory measures to protect his railroad supply lines as he moved through Georgia in 1864. In the final stages of the Civil War, guerrilla activities became an acute problem for areas in which civil authority had broken down. Irregular bands terrorized and plundered farms and towns, killing or wounding large numbers of people.

Guerrilla Activity in North Georgia

In 1863 Georgia governor Joseph E. Brown responded to such complaints by dispatching parties of state and Confederate soldiers into mountain counties to track down and arrest dozens of disloyal civilians. These same counties also responded to local disturbances by forming safety committees and home guard companies to protect them from “tories,” or Unionists. Unionist guerrillas had their own support networks of civilians, particularly in such northern counties as Fannin, where anti-Confederate feelings were widespread.

In an effort to control guerrilla organizations and maintain order in north Georgia, Governor Brown granted commissions authorizing mounted commands to the region. Brown also attempted to address the problem of lawless bands of men stealing property from civilians around the state. The governor was careful not to accuse any of the bands raised under his authority with these crimes, noting that the lawless men often misidentified themselves as Confederate cavalrymen under General Joseph Wheeler.

Guerrilla Activity in South Georgia

Sherman’s Response to Guerrillas

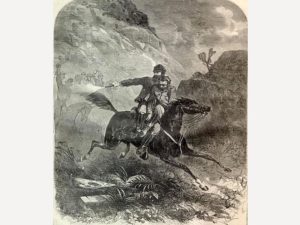

As Sherman’s troops advanced into northwest Georgia during the 1864 Atlanta Campaign, they encountered Confederate guerrillas intent on disrupting the Western and Atlantic Railroad, the Union’s main supply line. Sherman declared that such activity was criminal and that guerrillas behaved like animals in their flouting of the conventions of war. Union general James B. Steedman, given responsibility for protecting the Western and Atlantic in late June 1864, attempted to fulfill his duty by issuing orders that any citizens found within three miles of the railroad be arrested and tried as spies. Despite such measures, Confederate partisans and guerrillas continually cut telegraph lines and partially disabled the railroad, although Union repair crews usually restored the lines in a timely fashion.

During the Atlanta campaign and the subsequent March to the Sea, Sherman employed a policy of punishing civilians for guerrilla activity. If guerrillas or bushwhackers struck at Union forces or attempted to impede their march by destroying bridges and obstructing roads, Sherman often ordered the destruction of houses in the vicinity. Some of the harshest reprisals for the attacks of guerrillas and Confederate cavalry scouts took place in the fall of 1864, when Union troops burned much of the town of Cassville, in Bartow County, and portions of other towns in northwest Georgia.

Surrender and Paroles

In early February 1865 Confederate general W. T. Wofford arrived in north Georgia, raising the hopes of civilians that law and order might be restored in their region. Wofford estimated that between 3,000 and 5,000 men in north Georgia belonged in the Confederate army, and he claimed that they would soon be organized not only to resist enemy raids but also to assume the offensive. Wofford’s subsequent actions suggest that his primary goal was to restore law and order in his native region.

Wofford surrendered all Confederate forces in north Georgia at Kingston, in Bartow County, on May 12, 1865. In the preceding weeks, Wofford had attempted to meet with roughly 500 guerrillas who had refused to obey his orders to surrender. Union general Henry M. Judah, who had negotiated with Wofford, announced that anyone who did not surrender would be considered an outlaw.

Judah believed that his ultimatum resulted in the capitulation of most guerrillas in north Georgia. The decision made in May 1865 by thousands of home guard soldiers to travel to Kingston to surrender and receive parole suggests some degree of continued affiliation with the Confederate army.

Content retrieved from: https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/history-archaeology/guerrilla-warfare-during-civil-war.