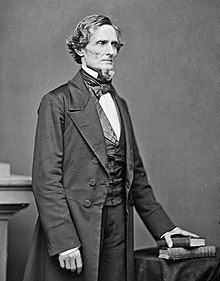

Jefferson Finis Davis (June 3, 1808 – December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America from 1861 to 1865. As a member of the Democratic Party, he represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives prior to switching allegiance to the Confederacy. He was appointed as the United States Secretary of War, serving from 1853 to 1857, under President Franklin Pierce.

Jefferson Finis Davis (June 3, 1808 – December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America from 1861 to 1865. As a member of the Democratic Party, he represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives prior to switching allegiance to the Confederacy. He was appointed as the United States Secretary of War, serving from 1853 to 1857, under President Franklin Pierce.Many historians attribute some of the Confederacy’s weaknesses to the poor leadership of Davis.[4] His preoccupation with detail, reluctance to delegate responsibility, lack of popular appeal, feuds with powerful state governors and generals, favoritism toward old friends, inability to get along with people who disagreed with him, neglect of civil matters in favor of military ones, and resistance to public opinion all worked against him.[5][6] Historians agree he was a much less effective war leader than his Union counterpart, President Abraham Lincoln. After Davis was captured in 1865, he was accused of treason and imprisoned at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. He was never tried and was released after two years. While not disgraced, Davis had been displaced in ex-Confederate affection after the war by his leading general, Robert E. Lee. Davis wrote a memoir entitled The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, which he completed in 1881. By the late 1880s, he began to encourage reconciliation, telling Southerners to be loyal to the Union. Ex-Confederates came to appreciate his role in the war, seeing him as a Southern patriot. He became a hero of the Lost Cause of the Confederacy in the post-Reconstruction South.[7]

President of the Confederate States of America

Anticipating a call for his services since Mississippi had seceded, Davis had sent a telegraph message to Governor John J. Pettus saying, “Judge what Mississippi requires of me and place me accordingly.”[81] On January 23, 1861, Pettus made Davis a major general of the Army of Mississippi.[14] On February 9, a constitutional convention met at Montgomery, Alabama, and considered Davis and Robert Toombs of Georgia as a possible president. Davis, who had widespread support from six of the seven states, easily won. He was seen as the “champion of a slave society and embodied the values of the planter class”, and was elected provisional Confederate President by acclamation.[82][83] He was inaugurated on February 18, 1861.[84][85] Alexander H. Stephens was chosen as Vice President, but he and Davis feuded constantly.[86]

Davis was the first choice because of his strong political and military credentials. He wanted to serve as commander-in-chief of the Confederate armies but said he would serve wherever directed.[87] His wife Varina Davis later wrote that when he received word that he had been chosen as president, “Reading that telegram he looked so grieved that I feared some evil had befallen our family.”[88]

Several forts in Confederate territory remained in Union hands. Davis sent a commission to Washington with an offer to pay for any federal property on Southern soil, as well as the Southern portion of the national debt, but Lincoln refused to meet with the commissioners. Brief informal discussions did take place with Secretary of State William Seward through Supreme Court Justice John A. Campbell, the latter of whom later resigned from the federal government, as he was from Alabama. Seward hinted that Fort Sumter would be evacuated, but gave no assurance.[89]

On March 1, 1861, Davis appointed General P. G. T. Beauregard to command all Confederate troops in the vicinity of Charleston, South Carolina, where state officials prepared to take possession of Fort Sumter. Beauregard was to prepare his forces but await orders to attack the fort. Within the fort the issue was not of the niceties of geopolitical posturing but of survival. They would be out of food on the 15th. The small Union garrison had but half a dozen officers and 127 soldiers under Major Robert Anderson. Famously, this included the baseball folk hero Captain (later major general) Abner Doubleday. More improbable yet was a Union officer who had the name of Jefferson C. Davis. He would spend the war being taunted for his name but not his loyalty to the Northern cause. The newly installed President Lincoln, not wishing to initiate hostilities, informed South Carolina Governor Pickens that he was dispatching a small fleet of ships from the navy yard in New York to resupply but not re-enforce Fort Pickens in Florida and Fort Sumter. The U.S. President did not inform CSA President Davis of this intended resupply of food and fuel. For Lincoln, Davis, as the leader of an insurrection, was without legal standing in U.S. affairs. To deal with him would be to give legitimacy to the rebellion. The fact that Sumter was the property of the sovereign United States was the reason for maintaining the garrison on the island fort. He informed Pickens that the resupply mission would not land troops or munitions unless they were fired upon. As it turned out, just as the supply ships approached Charleston harbor, the bombardment would begin and the flotilla watched the spectacle from 10 miles (16 km) at sea.

Davis faced the most important decision of his career: to prevent reinforcement at Fort Sumter or to let it take place. He and his cabinet decided to demand that the Federal garrison surrender and, if this was refused, to use military force to prevent reinforcement before the fleet arrived. Anderson did not surrender. With Davis’s endorsement, Beauregard began the bombarding of the fort in the early dawn of April 12. The Confederates continued their artillery attack on Fort Sumter until it surrendered on April 14. No one was killed in the artillery duel, but the attack on the U.S. fort meant the fighting had started. President Lincoln called up 75,000 state militiamen to march south to recapture Federal property. In the North and South, massive rallies were held to demand immediate war. The Civil War had begun.[90][91][92][93]

Overseeing the Civil War efforts

When Virginia joined the Confederacy, Davis moved his government to Richmond in May 1861. He and his family took up his residence there at the White House of the Confederacy later that month.[94] Having served since February as the provisional president, Davis was elected to a full six-year term on November 6, 1861, and was inaugurated on February 22, 1862.[95]

At the start of the war, nearly 21 million people lived in the North compared to 9 million in the South. While the North’s population was almost entirely white, the South had an enormous number of black slaves and people of color. While the latter were free, becoming a soldier was seen as the prerogative of white men only. Many Southerners were terrified at the idea of a black man with a gun. Excluding old men and boys, the white males available for Confederate service were less than two million. There was also the additional burden that the near four million black slaves had to be heavily policed as there was no trust between the owner and “owned”. The North had vastly greater industrial capacity; built nearly all the locomotives, steamships, and industrial machinery; and had a much larger and more integrated railroad system. Nearly all the munitions facilities were in the North, while critical ingredients for gunpowder were in very short supply in the South.

Much of the railroad track that existed in the Confederacy was of simple railway design just meant to carry the large bales of cotton to local river ports in the harvest season. These often did not connect to other rail-lines, making internal shipments of goods difficult at best. While the Union had a large navy, the new Confederate Navy had only a few captured warships or newly built vessels. These did surprisingly well but ultimately were sunk or abandoned as the Union Navy controlled more rivers and ports. Rebel ‘raiders’ loosed on the Northern ships on the Atlantic did tremendous damage and sent Yankee ships into safe harbors as insurance rates soared. The Union blockade of the South, however, made imports via blockade runners difficult and expensive. Somewhat awkwardly, these runners didn’t bring significant amounts of the war materials, so greatly needed, but rather the European luxuries sought as a relief from the privations of the wartime’s stark conditions.[96][97]

In June 1862, Davis was forced to assign General Robert E. Lee to replace the wounded Joseph E. Johnston to command of the Army of Northern Virginia, the main Confederate army in the Eastern Theater. That December Davis made a tour of Confederate armies in the west of the country. He had a very small circle of military advisers. He largely made the main strategic decisions on his own, though he had special respect for Lee’s views. Given the Confederacy’s limited resources compared with the Union, Davis decided that the Confederacy would have to fight mostly on the strategic defensive. He maintained this outlook throughout the war, paying special attention to the defense of his national capital at Richmond. He approved Lee’s strategic offensives when he felt that military success would both shake Northern self-confidence and strengthen the peace movements there. However, the several campaigns invading the North were met with defeat. A bloody battle at Antietam in Maryland as well as the ride into Kentucky, the Confederate Heartland Offensive (both in 1862)[98] drained irreplaceable men and talented officers. A final offense led to the three-day bloodletting at Gettysburg in Pennsylvania (1863),[99] crippling the South still further. The status of techniques and munitions made the defensive side much more likely to endure: an expensive lesson vindicating Davis’s initial belief.

Administration and cabinet

As provisional president in 1861, Davis formed his first cabinet. Robert Toombs of Georgia was the first Secretary of State and Christopher Memminger of South Carolina became Secretary of the Treasury. LeRoy Pope Walker of Alabama was made Secretary of War, after being recommended for this post by Clement Clay and William Yancey (both of whom declined to accept cabinet positions themselves). John Reagan of Texas became Postmaster General. Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana became Attorney General. Although Stephen Mallory was not put forward by the delegation from his state of Florida, Davis insisted that he was the best man for the job of Secretary of the Navy, and he was eventually confirmed.[100]

Since the Confederacy was founded, among other things, on states’ rights, one important factor in Davis’s choice of cabinet members was representation from the various states. He depended partly upon recommendations from congressmen and other prominent people. This helped maintain good relations between the executive and legislative branches. This also led to complaints as more states joined the Confederacy, however, because there were more states than cabinet positions.[101]

As the war progressed, this dissatisfaction increased and there were frequent changes to the cabinet. Toombs, who had wished to be president himself, was frustrated as an advisor and resigned within a few months of his appointment to join the army. Robert Hunter of Virginia replaced him as Secretary of State on July 25, 1861.[102] On September 17, Walker resigned as Secretary of War due to a conflict with Davis, who had questioned his management of the War Department and had suggested he consider a different position. Walker requested, and was given, command of the troops in Alabama. Benjamin left the Attorney General position to replace him, and Thomas Bragg of North Carolina (brother of General Braxton Bragg) took Benjamin’s place as Attorney General.[103]

Following the November 1861 election, Davis announced the permanent cabinet in March 1862. Benjamin moved again, to Secretary of State. George W. Randolph of Virginia had been made the Secretary of War. Mallory continued as Secretary of the Navy and Reagan as Postmaster General. Both kept their positions throughout the war. Memminger remained Secretary of the Treasury, while Thomas Hill Watts of Alabama was made Attorney General.[104]

In 1862 Randolph resigned from the War Department, and James Seddon of Virginia was appointed to replace him. In late 1863, Watts resigned as Attorney General to take office as the Governor of Alabama, and George Davis of North Carolina took his place. In 1864, Memminger withdrew from the Treasury post due to congressional opposition, and was replaced by George Trenholm of South Carolina. In 1865 congressional opposition likewise caused Seddon to withdraw, and he was replaced by John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky.[105]

Cotton was the South’s primary export and the basis of its economy and the system of production the South used was dependent upon slave labor. At the outset of the Civil War, Davis realized that intervention from European powers would be vital if the Confederacy was to stand against the Union. The administration sent repeated delegations to European nations, but several factors prevented Southern success in terms of foreign diplomacy. The Union blockade of the Confederacy led European powers to remain neutral, contrary to the Southern belief that a blockade would cut off the supply of cotton to Britain and other European nations and prompt them to intervene on behalf of the South. Many European countries objected to slavery. Britain had abolished it in the 1830s, and Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 made support for the South even less appealing in Europe. Finally, as the war progressed and the South’s military prospects dwindled, foreign powers were not convinced that the Confederacy had the strength to become independent. In the end, not a single foreign nation recognized the Confederate States of America.[106]

Strategic failures

Most historians sharply criticize Davis for his flawed military strategy, his selection of friends for military commands, and his neglect of homefront crises.[107][108] Until late in the war, he resisted efforts to appoint a general-in-chief, essentially handling those duties himself. “Davis was loathed by much of his military, Congress and the public — even before the Confederacy died on his watch,” and General Beauregard wrote in a letter: “If he were to die today, the whole country would rejoice at it.”[109]

On January 31, 1865, Lee assumed this role, but it was far too late. Davis insisted on a strategy of trying to defend all Southern territory with ostensibly equal effort. This diluted the limited resources of the South and made it vulnerable to coordinated strategic thrusts by the Union into the vital Western Theater (e.g., the capture of New Orleans in early 1862). He made other controversial strategic choices, such as allowing Lee to invade the North in 1862 and 1863 while the Western armies were under very heavy pressure. When Lee lost at Gettysburg, Vicksburg simultaneously fell, and the Union took control of the Mississippi River, splitting the Confederacy. At Vicksburg, the failure to coordinate multiple forces on both sides of the Mississippi River rested primarily on Davis’s inability to create a harmonious departmental arrangement or to force such generals as Edmund Kirby Smith, Earl Van Dorn, and Theophilus H. Holmes to work together.[110] In fact, during the late stages of the Franklin–Nashville Campaign, Davis warned Beauregard that Kirby Smith would prove uncooperative to whatever proposal the Creole general had in mind for him.[111]

Davis has been faulted for poor coordination and management of his generals. This includes his reluctance to resolve a dispute between Leonidas Polk, a personal friend, and Braxton Bragg, who was defeated in important battles and distrusted by his subordinates.[112] He was similarly reluctant to relieve the capable but overcautious Joseph E. Johnston until, after numerous frustrations which he detailed in a March 1, 1865 letter to Col. James Phelan of Mississippi, he replaced him with John Bell Hood,[113][114] a fellow Kentuckian who had shared the Confederate President’s views on aggressive military policies.[115]

Davis gave speeches to soldiers and politicians but largely ignored the common people, who came to resent the favoritism shown to the rich and powerful; Davis thus failed to harness Confederate nationalism.[116] One historian speaks of “the heavy-handed intervention of the Confederate government.” Economic intervention, regulation, and state control of manpower, production and transport were much greater in the Confederacy than in the Union.[117] Davis did not use his presidential pulpit to rally the people with stirring rhetoric; he called instead for people to be fatalistic and to die for their new country.[118] Apart from two month-long trips across the country where he met a few hundred people, Davis stayed in Richmond where few people saw him; newspapers had limited circulation, and most Confederates had little favorable information about him.[119]

To finance the war, the Confederate government initially issued bonds, but investment from the public never met the demands. Taxes were lower than in the Union and collected with less efficiency; European investment was also insufficient. As the war proceeded, both the Confederate government and the individual states printed more and more paper money. Inflation increased from 60% in 1861 to 300% in 1863 and 600% in 1864. Davis did not seem to grasp the enormity of the problem.[120][121]

In April 1863, food shortages led to rioting in Richmond, as poor people robbed and looted numerous stores for food until Davis cracked down and restored order.[122] Davis feuded bitterly with his vice president. Perhaps even more seriously, he clashed with powerful state governors who used states’ rights arguments to withhold their militia units from national service and otherwise blocked mobilization plans.[123]

Davis is widely evaluated as a less effective war leader than Lincoln, even though Davis had extensive military experience and Lincoln had little. Davis would have preferred to be an army general and tended to manage military matters himself. Lincoln and Davis led in very different ways. According to one historian,

There were many factors that led to Union victory over the Confederacy, and Davis recognized from the start that the South was at a distinct disadvantage; but in the end, Lincoln helped to achieve victory, whereas Davis contributed to defeat.[124]

Final days of the Confederacy

In March 1865, General Order 14 provided for enlisting slaves into the army, with a promise of freedom for service. The idea had been suggested years earlier, but Davis did not act upon it until late in the war, and very few slaves were enlisted.[125]

On April 3, with Union troops under Ulysses S. Grant poised to capture Richmond, Davis escaped to Danville, Virginia, together with the Confederate Cabinet, leaving on the Richmond and Danville Railroad. Lincoln was in Davis’s Richmond office just 40 hours later. William T. Sutherlin turned over his mansion, which served as Davis’s temporary residence from April 3 to April 10, 1865.[126] On about April 12, Davis received Robert E. Lee’s letter announcing surrender.[127] He issued his last official proclamation as president of the Confederacy, and then went south to Greensboro, North Carolina.[128]

After Lee’s surrender, a public meeting was held in Shreveport, Louisiana, at which many speakers supported continuation of the war. Plans were developed for the Davis government to flee to Havana, Cuba. There, the leaders would regroup and head to the Confederate-controlled Trans-Mississippi area by way of the Rio Grande.[129] None of these plans were put into practice.

On April 14, Lincoln was shot, dying the next day. Davis expressed regret at his death. He later said that he believed Lincoln would have been less harsh with the South than his successor, Andrew Johnson.[130] In the aftermath, Johnson issued a $100,000 reward for the capture of Davis and accused him of helping to plan the assassination. As the Confederate military structure fell into disarray, the search for Davis by Union forces intensified.[131]

President Davis met with his Confederate Cabinet for the last time on May 5, 1865, in Washington, Georgia, and officially dissolved the Confederate government.[132] The meeting took place at the Heard house, the Georgia Branch Bank Building, with 14 officials present. Along with their hand-picked escort led by Given Campbell, Davis and his wife Varina Davis were captured by Union forces on May 10 at Irwinville in Irwin County, Georgia.[133]

Mrs. Davis recounted the circumstances of her husband’s capture as described below: “Just before day the enemy charged our camp yelling like demons … I pleaded with him to let me throw over him a large waterproof wrap which had often served him in sickness during the summer season for a dressing gown and which I hoped might so cover his person that in the grey of the morning he would not be recognized. As he strode off I threw over his head a little black shawl which was around my own shoulders, saying that he could not find his hat and after he started sent my colored woman after him with a bucket for water hoping that he would pass unobserved.”[134]:172

It was reported in the media that Davis put his wife’s overcoat over his shoulders while fleeing. This led to the persistent rumor that he attempted to flee in women’s clothes, inspiring caricatures that portrayed him as such.[135] Over 40 years later, an article in the Washington Herald claimed that Mrs. Davis’s heavy shawl had been placed on Davis who was “always extremely sensitive to cold air”, to protect him from the “chilly atmosphere of the early hour of the morning” by the slave James Henry Jones, Davis’s valet who served Davis and his family during and after the Civil War.[136] Meanwhile, Davis’s belongings continued on the train bound for Cedar Key, Florida. They were first hidden at Senator David Levy Yulee’s plantation in Florida, then placed in the care of a railroad agent in Waldo. On June 15, 1865, Union soldiers seized Davis’s personal baggage from the agent, together with some of the Confederate government’s records. A historical marker was erected at this site.[137][138][139] In 1939, Jefferson Davis Memorial Historic Site was opened to mark the place where Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured.

Imprisonment

On May 19, 1865, Davis was imprisoned in a casemate at Fortress Monroe, on the coast of Virginia. Irons were riveted to his ankles at the order of General Nelson Miles, who was in charge of the fort. Davis was allowed no visitors, and no books except the Bible. He became sicker, and the attending physician warned that his life was in danger, but this treatment continued for some months until late autumn when he was finally given better quarters. General Miles was transferred in mid-1866, and Davis’s treatment continued to improve.[140]

Pope Pius IX (see Pope Pius IX and the United States), after learning that Davis was a prisoner, sent him a portrait inscribed with the Latin words “Venite ad me omnes qui laboratis, et ego reficiam vos, dicit Dominus”, which correspond to Matthew 11:28,[141][142] “Come to me, all you that labor, and are burdened, and I will refresh you, sayeth the Lord”. A hand-woven crown of thorns associated with the portrait is often said to have been made by the Pope[143][144] but may have been woven by Davis’s wife Varina.[145]

Varina and their young daughter Winnie were allowed to join Davis, and the family was eventually given an apartment in the officers’ quarters. Davis was indicted for treason while imprisoned; one of his attorneys was ex-Governor Thomas Pratt of Maryland.[146] There was a great deal of discussion in 1865 about bringing treason trials, especially against Jefferson Davis. While there was no consensus in President Johnson’s cabinet to do so, on June 11, 1866 the House of Representatives voted, 105-19, to support such a trial against Davis. Although Davis wanted such a trial for himself, there were no treason trials against anyone, as it was felt they would probably not succeed and would impede reconciliation. There was also a concern at the time that such action could result in a judicial decision that would validate the constitutionality of secession (later removed by the Supreme Court ruling in Texas v. White (1869) declaring secession unconstitutional).[147][148][149][150]

A jury of 12 black and 12 white men was recruited by United States Circuit Court judge John Curtiss Underwood in preparation for the trial.[151]

After two years of imprisonment, Davis was released on bail of $100,000, which was posted by prominent citizens including Horace Greeley, Cornelius Vanderbilt and Gerrit Smith.[152] (Smith was a member of the Secret Six who financially supported abolitionist John Brown.) Davis went to Montreal, Quebec to join his family which had fled there earlier, and lived in Lennoxville, Quebec until 1868,[153] also visiting Cuba and Europe in search of work.[154] At one stage he stayed as a guest of James Smith, a foundry owner in Glasgow, who had struck up a friendship with Davis when he toured the Southern States promoting his foundry business.[155] Davis remained under indictment until Andrew Johnson issued on Christmas Day of 1868 a presidential “pardon and amnesty” for the offense of treason to “every person who directly or indirectly participated in the late insurrection or rebellion” and after a federal circuit court on February 15, 1869, dismissed the case against Davis after the government’s attorney informed the court that he would no longer continue to prosecute Davis.[147][148][149]

Content retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jefferson_Davis.