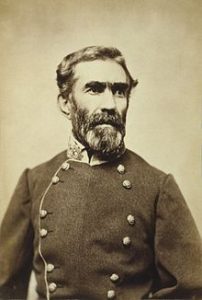

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who was assigned to duty at Richmond, under direction of the President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, and charged with the conduct of military operations of the armies of the Confederate States from February 24, 1864, until January 13, 1865, when he was charged with command and defense of Wilmington, North Carolina. He previously had command of an army in the Western Theater.

Braxton Bragg (March 22, 1817 – September 27, 1876) was a senior officer of the Confederate States Army who was assigned to duty at Richmond, under direction of the President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, and charged with the conduct of military operations of the armies of the Confederate States from February 24, 1864, until January 13, 1865, when he was charged with command and defense of Wilmington, North Carolina. He previously had command of an army in the Western Theater.

Bragg, a native of Warrenton, North Carolina, was educated at West Point and became an artillery officer. He served in Florida and then received three brevet promotions for distinguished service in the Mexican–American War, most notably the Battle of Buena Vista.

He established a reputation as a strict disciplinarian, but also as a junior officer willing to publicly argue with and criticize his superior officers, including those at the highest levels of the Army. After a series of posts in the Indian Territory, he resigned from the U.S. Army in 1856 to become a sugar plantation slave owner in Louisiana.

During the Civil War, Bragg trained soldiers in the Gulf Coast region. He was a corps commander at the Battle of Shiloh and subsequently was named to command the Army of Mississippi (later known as the Army of Tennessee).

He and Edmund Kirby Smith attempted an invasion of Kentucky in 1862, but Bragg retreated following the inconclusive Battle of Perryville, Kentucky, in October. In December, he fought another inconclusive battle at Murfreesboro, Tennessee, the Battle of Stones River, but once again withdrew his army. In 1863, he fought a series of battles against Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans and the Union Army of the Cumberland.

In June, he was outmaneuvered in the Tullahoma Campaign and retreated into Chattanooga. In September, he was forced to evacuate Chattanooga, but counterattacked Rosecrans and defeated him at the Battle of Chickamauga, the bloodiest battle in the Western Theater, and the only major Confederate victory therein. In November, Bragg’s army was routed in turn by Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in the Battles for Chattanooga.

Throughout these campaigns, Bragg fought almost as bitterly against some of his uncooperative subordinates as he did against the enemy, and they made multiple attempts to have him replaced as army commander. The defeat at Chattanooga was the last straw, and Bragg was recalled in early 1864 to Richmond, where he became the military adviser to Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Near the end of the war, he defended the region surrounding Fort Fisher near Wilmington, North Carolina, and served as a corps commander in the Carolinas Campaign. After the war, Bragg worked as the superintendent of the New Orleans waterworks, a supervisor of harbor improvements at Mobile, Alabama, and as a railroad engineer and inspector in Texas.

Bragg is generally considered among the worst generals of the Civil War. Although his commands often outnumbered those he fought against, most of the battles in which he engaged ended in defeats. The only exception was Chickamauga, which was largely due to the timely arrival of Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s corps.

Some historians fault Bragg as a commander for impatience and poor treatment of others. Some, however, point towards the failures of Bragg’s subordinates, especially Leonidas Polk, a close ally of Davis and known enemy of Bragg, as the more significant factors in the many Confederate defeats at which Bragg commanded.

American Civil War

Before the start of the Civil War, Bragg was a colonel in the Louisiana Militia. On December 12, 1860, Governor Thomas O. Moore appointed him to the state military board, an organization charged with creating a 5,000-man army. He took the assignment, even though he had been opposed to secession. On January 11, 1861, Bragg led a group of 500 volunteers to Baton Rouge, where they persuaded the commander of the federal arsenal there to surrender. The state convention on secession also established a state army and Moore appointed Bragg its commander, with the rank of major general, on February 20, 1861. He commanded the forces around New Orleans until April 16, but his commission was transferred to be a brigadier general of the Confederate States Army on March 7, 1861. He commanded forces in Pensacola, Florida, Alabama, and the Department of West Florida and was promoted to major general on September 12, 1861. His tenure was successful and he trained his men to be some of the best disciplined troops in the Confederate Army, such as the 5th Georgia and the 6th Florida Regiments.[18][19][20][21]

In December, President Davis asked Bragg to take command of the Trans-Mississippi Department, but Bragg declined. He was concerned for the prospects of victory west of the Mississippi River and about the poorly supplied and ill-disciplined troops there. He was also experiencing one of his periodic episodes of ill health that would plague him throughout the war. For years he had suffered from rheumatism, dyspepsia, nerves, and severe migraine headaches, ailments that undoubtedly contributed to his disagreeable personal style. The command went to Earl Van Dorn. Bragg proposed to Davis that he change his strategy of attempting to defend every square mile of Confederate territory, recommending that his troops were of less value on the Gulf Coast than they would be farther to the north, concentrated with other forces for an attack against the Union Army in Tennessee. Bragg transported about 10,000 men to Corinth, Mississippi, in February 1862 and was charged with improving the poor discipline of the Confederate troops already assembled under General Albert Sidney Johnston.[22]

Battle of Shiloh

Bragg commanded a corps (and was also chief of staff) under Johnston at the Battle of Shiloh, April 6–7, 1862. In the initial surprise Confederate advance, Bragg’s corps was ordered to attack in a line that was almost 3 miles (4.8 km) long, but he soon began directing activities of the units that found themselves around the center of the battlefield. His men became bogged down against a Union salient called the Hornet’s Nest, which he attacked for hours with piecemeal frontal assaults. After Johnston was killed in the battle, General P. G. T. Beauregard assumed command, and appointed Bragg his second in command. Bragg was dismayed when Beauregard called off a late afternoon assault against the Union’s final position, which was strongly defended, calling it their last opportunity for victory. On the second day of battle, the Union army counterattacked and the Confederates retreated back to Corinth.[23]

Bragg received public praise for his conduct in the battle and on April 12, 1862, Jefferson Davis appointed Bragg a full general, the sixth man to achieve that rank and one of only seven in the history of the Confederacy.[24] His date of rank was April 6, 1862, coinciding with the first day at Shiloh. After the Siege of Corinth, Beauregard departed on sick leave, leaving Bragg in temporary command of the army in Tupelo, Mississippi, but Beauregard failed to inform President Davis of his departure and spent two weeks absent without leave. Davis was looking for someone to replace Beauregard because of his perceived poor performance at Corinth, and the opportunity presented itself when Beauregard left without permission. Bragg was then appointed his successor as commander of the Western Department (known formally as Department Number Two), including the Army of Mississippi, on June 17, 1862.[25]

Battle of Perryville

In August 1862, Confederate Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith decided to invade Kentucky from Eastern Tennessee, hoping that he could arouse supporters of the Confederate cause in the border state and draw the Union forces under Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, beyond the Ohio River. Bragg considered various options, including an attempt to retake Corinth, or to advance against Buell’s army through Middle Tennessee. He eventually heeded Kirby Smith’s calls for reinforcement and decided to relocate his Army of Mississippi to join with him. He moved 30,000 infantrymen in a tortuous railroad journey from Tupelo through Mobile and Montgomery to Chattanooga, while his cavalry and artillery moved by road. Although Bragg was the senior general in the theater, President Davis had established Kirby Smith’s Department of East Tennessee as an independent command, reporting directly to Richmond. This decision caused Bragg difficulty during the campaign.[26]

Smith and Bragg met in Chattanooga on July 31, 1862, and devised a plan for the campaign: Kirby Smith’s Army of Kentucky would first march into Kentucky to dispose of the Union defenders of Cumberland Gap. (Bragg’s army was too exhausted from its long journey to begin immediate offensive operations.) Smith would return to join Bragg, and their combined forces would attempt to maneuver into Buell’s rear and force a battle to protect his supply lines. Once the armies were combined, Bragg’s seniority would apply and Smith would be under his direct command. Assuming that Buell’s army could be destroyed, Bragg and Smith would march farther north into Kentucky, a movement they assumed would be welcomed by the local populace. Any remaining Federal force would be defeated in a grand battle in Kentucky, establishing the Confederate frontier at the Ohio River.[27]

On August 9, Smith informed Bragg that he was breaking the agreement and intended to bypass Cumberland Gap, leaving a small holding force to neutralize the Union garrison, and to move north. Unable to command Smith to honor their plan, Bragg focused on a movement to Lexington instead of Nashville. He cautioned Smith that Buell could pursue and defeat his smaller army before Bragg’s army could join up with them.[28]

Bragg departed from Chattanooga on August 27, just before Smith reached Lexington. On the way, he was distracted by the capture of a Union fort at Munfordville. He had to decide whether to continue toward a fight with Buell (over Louisville) or rejoin Smith, who had gained control of the center of the state by capturing Richmond and Lexington, and threatened to move on Cincinnati. Bragg chose to rejoin Smith. He left his army and met Smith in Frankfort, where they attended the inauguration of Confederate Governor Richard Hawes on October 4. The inauguration ceremony was disrupted by the sound of approaching Union cannon fire and the organizers canceled the inaugural ball scheduled for that evening.[29]

On October 8, the armies met unexpectedly at the Battle of Perryville; they had skirmished the previous day as they were searching for water sources in the vicinity. Bragg ordered the wing of his army under Maj. Gen. Leonidas Polk to attack what he thought was an isolated portion of Buell’s command, but had difficulty motivating Polk to begin the fight until Bragg arrived in person. Eventually Polk attacked the corps of Maj. Gen. Alexander M. McCook on the Union army’s left flank and forced it to fall back. By the end of the day, McCook had been driven back about a mile, but reinforcements had arrived to stabilize the line, and Bragg only then began to realize that his limited tactical victory in the bloody battle had been against less than half of Buell’s army and the remainder was arriving quickly.[30]

Kirby Smith pleaded with Bragg to follow up on his success: “For God’s sake, General, let us fight Buell here.” Bragg replied, “I will do it, sir,” but then displaying what one observer called “a perplexity and vacillation which had now become simply appalling to Smith, to Hardee, and to Polk,”[31] he ordered his army to retreat through the Cumberland Gap to Knoxville. Bragg referred to his retreat as a withdrawal, the successful culmination of a giant raid. He had multiple reasons for withdrawing. Disheartening news had arrived from northern Mississippi that Earl Van Dorn and Sterling Price had been defeated at Corinth, just as Robert E. Lee had failed in his Maryland Campaign. He saw that his army had not much to gain from a further, isolated victory, whereas a defeat might cost not only the bountiful food and supplies yet collected, but also his army. He wrote to his wife, “With the whole southwest thus in the enemy’s possession, my crime would have been unpardonable had I kept my noble little army to be ice-bound in the northern clime, without tents or shoes, and obliged to forage daily for bread, etc.”[32] He was quickly called to Richmond to explain to Jefferson Davis the charges brought by his officers about how he had conducted his campaign, demanding that he be replaced as head of the army. Although Davis decided to leave the general in command, Bragg’s relationship with his subordinates would be severely damaged. Upon rejoining the army, he ordered a movement to Murfreesboro, Tennessee.[33]

Battle of Stones River

Bragg renamed his force as the Army of Tennessee on November 20. On November 24 Don Carlos Buell was replaced in command of the Union Army of the Ohio by Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, who immediately renamed it the Army of the Cumberland. In late December, Rosecrans advanced from Nashville against Bragg’s position at Murfreesboro. Before Rosecrans could attack, Bragg launched a strong surprise attack against Rosecrans’s right flank on December 31, 1862, the start of the Battle of Stones River. The Confederates succeeded in driving the Union army back to a small defensive position, but could not destroy it, nor could they break its supply line to Nashville, as Bragg intended. Despite this, Bragg considered the first day of battle to be a victory and assumed that Rosecrans would soon retreat. By January 2, 1863, however, the Union troops remained in place and the battle resumed as Bragg launched an unsuccessful attack by the troops of Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge against the well-defended Union left flank. Recognizing his lack of progress, the severe winter weather, the arrival of supplies and reinforcements for Rosecrans, and heeding the recommendations of corps commanders Hardee and Polk, Bragg withdrew his army from the field to Tullahoma, Tennessee.[34]

Bragg’s generals were vocal in their dissatisfaction with his command during the Kentucky campaign and Stones River. He reacted to the rumors of criticism by circulating a letter to his corps and division commanders that asked them to confirm in writing that they had recommended withdrawing after the latter battle, stating that if he had misunderstood them and withdrawn mistakenly, he would willingly step down. Unfortunately, he wrote the letter at a time that a number of his most faithful supporters were on leave for illness or wounds.[36] Bragg’s critics, including William J. Hardee, interpreted the letter as having an implied secondary question—had Bragg lost the confidence of his senior commanders? Leonidas Polk did not reply to the implied question, but he wrote directly to his friend, Jefferson Davis, recommending that Bragg be replaced.[37]

Davis responded to the complaints by dispatching Gen. Joseph E. Johnston to investigate the condition of the army. Davis assumed that Johnston, Bragg’s superior, would find the situation wanting and take command of the army in the field, easing Bragg aside. However, Johnston arrived on the scene and found the men of the Army of Tennessee in relatively good condition. He told Bragg that he had “the best organized, armed, equipped, and disciplined army in the Confederacy.”[38] Johnston explicitly refused any suggestion that he take command, concerned that people would think he had taken advantage of the situation for his own personal gain. When Davis ordered Johnston to send Bragg to Richmond, Johnston delayed because of Elise Bragg’s illness; when her health improved Johnston was unable to assume command because of lingering medical problems from his wound at the Battle of Seven Pines in 1862.[39]

Tullahoma Campaign

As Bragg’s army fortified Tullahoma, Rosecrans spent the next six months in Murfreesboro, resupplying and retraining his army to resume its advance. Rosecrans’s initial movements on June 23 took Bragg by surprise. While keeping Polk’s corps occupied with small actions in the center of the Confederate line, Rosecrans sent the majority of his army around Bragg’s right flank. Bragg was slow to react and his subordinates were typically uncooperative: the mistrust among the general officers of the Army of Tennessee for the past months led to little direct communication about strategy, and neither Polk nor Hardee had a firm understanding of Bragg’s plans. As the Union army outmaneuvered the Confederates, Bragg was forced to abandon Tullahoma and on July 4 retreated behind the Tennessee River. Tullahoma is recognized as a “brilliant” campaign for Rosecrans, achieving with minimal losses his goal of driving Bragg from Middle Tennessee. Judith Hallock wrote that Bragg was “outfoxed” and that his ill health may have been partially to blame for his performance, but her overall assessment was that he performed credibly during the retreat from Tullahoma, keeping his army intact under difficult circumstances.[40]

Although the Army of Tennessee had about 52,000 men at the end of July, the Confederate government merged the Department of East Tennessee, under Maj. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, into Bragg’s Department of Tennessee, which added 17,800 men to Bragg’s army, but also extended his command responsibilities northward to the Knoxville area. This brought a third subordinate into Bragg’s command who had little or no respect for him.[41] Buckner’s attitude was colored by Bragg’s unsuccessful invasion of Buckner’s native Kentucky in 1862, as well as by the loss of his command through the merger.[42] A positive aspect for Bragg was Hardee’s request to be transferred to Mississippi in July, but he was replaced by Lt. Gen. D.H. Hill, a general who had not gotten along with Robert E. Lee in Virginia.[43]

The Confederate War Department asked Bragg in early August if he could assume the offensive against Rosecrans if he were given reinforcements from Mississippi. He demurred, concerned about the daunting geographical obstacles and logistical challenges, preferring to wait for Rosecrans to solve those same problems and attack him.[44] An opposed crossing of the Tennessee River was not feasible, so Rosecrans devised a deception to distract Bragg above Chattanooga while the army crossed downstream. Bragg was rightfully concerned about a sizable Union force under Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside that was threatening Knoxville to the northeast, and Rosecrans reinforced this concern by feinting to his left and shelling the city of Chattanooga from the heights north of the river. The bulk of the Union army crossed the Tennessee southeast of Chattanooga by September 4 and Bragg realized that his position there was no longer tenable. He evacuated the city on September 8.[45]

Battle of Chickamauga

After Rosecrans had consolidated his gains and secured his hold on Chattanooga, he began moving his army into northern Georgia in pursuit of Bragg. Bragg continued to suffer from the conduct of his subordinates, who were not attentive to his orders. On September 10, Maj. Gens. Thomas C. Hindman and D.H. Hill refused to attack, as ordered, an outnumbered Federal column at McLemore’s Cove (the Battle of Davis’s Cross Roads). On September 13, Bragg ordered Leonidas Polk to attack Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden’s corps, but Polk ignored the orders and demanded more troops, insisting that it was he who was about to be attacked. Rosecrans used the time lost in these delays to concentrate his scattered forces. Finally, on September 19–20, 1863, Bragg, reinforced by two divisions from Mississippi, one division and several brigades from the Department of East Tennessee, and two divisions under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet from Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, turned on the pursuing Rosecrans in northeastern Georgia and at high cost defeated him at the Battle of Chickamauga, the greatest Confederate victory in the Western Theater during the war. It was not a complete victory, however. Bragg’s objective was to cut off Rosecrans from Chattanooga and destroy his army. Instead, following a partial rout of the Union army by Longstreet’s wing, a stout defense by Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas allowed Rosecrans and almost all of his army to escape.[46]

After the battle, Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland retreated to Chattanooga, where Bragg laid siege to the city. He began to wage a battle against the subordinates he resented for failing him in the campaign—Hindman for his lack of action in McLemore’s Cove, and Polk for delaying the morning attack Bragg ordered on September 20. On September 29, Bragg suspended both officers from their commands. In early October, an attempted mutiny of Bragg’s subordinates resulted in D.H. Hill being relieved from his command. Longstreet was dispatched with his corps to the Knoxville Campaign against Ambrose Burnside, seriously weakening Bragg’s army at Chattanooga.[47]

Some of Bragg’s subordinate generals were frustrated at what they perceived to be his lack of willingness to exploit the victory by pursuing the Union army toward Chattanooga and destroying it. Polk in particular was outraged at being relieved of command. The dissidents, including many of the division and corps commanders, met in secret and prepared a petition to President Jefferson Davis. Although the author of the petition is not known, historians suspect it was Simon Buckner, whose signature was first on the list.[48] Lt. Gen. James Longstreet wrote to the Secretary of War with the prediction that “nothing but the hand of God can save us or help us as long as we have our present commander.” With the Army of Tennessee literally on the verge of mutiny, Jefferson Davis reluctantly traveled to Chattanooga to personally assess the situation and to try to stem the tide of dissent in the army. Although Bragg offered to resign to resolve the crisis,[49] Davis eventually decided to leave Bragg in command, denounced the other generals, and termed their complaints “shafts of malice”.[50]

Battles for Chattanooga

While Bragg fought with his subordinates and reduced his force by dispatching Longstreet to Knoxville, the besieged Union army received a new commander—Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant—and significant reinforcements from Mississippi and Virginia. The Battles for Chattanooga marked Bragg’s final days as an army commander. His weakened left flank (previously manned by Longstreet’s troops) fell on November 24 during the Battle of Lookout Mountain. The following day in the Battle of Missionary Ridge, his primary defensive line successfully resisted an attack on its right flank, but the center was overwhelmed in a frontal assault by George Thomas’s army. The Army of Tennessee was routed and retreated to Dalton, Georgia. Bragg offered his resignation on November 29 and was chagrined when Pres. Davis accepted it immediately. He turned over temporary command to Hardee on December 2 and was replaced with Joseph E. Johnston, who commanded the army in the 1864 Atlanta Campaign against William T. Sherman.[51]

Advisor to the President

In February 1864, Bragg was summoned to Richmond for consultation with Davis. The orders for his new assignment on February 24 read that he was “charged with the conduct of military operations of the Confederate States”, but he was essentially Davis’s military adviser or chief of staff without a direct command, a post once held by Robert E. Lee. Bragg used his organizational abilities to reduce corruption and improve the supply system. He took over responsibility for administration of the military prison system and its hospitals. He reshaped the Confederacy’s conscription process by streamlining the chain of command and reducing conscripts’ avenues of appeal. During his tenure in Richmond, he had numerous quarrels with significant figures, including the Secretary of War, the Commissary General, members of Congress, the press, and many of his fellow generals; the exception to the latter was Robert E. Lee, who treated Bragg politely and with deference and who had, Bragg knew, an exceptionally close relationship with the president.[53]

In May, while Lee was occupied defending against Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign in Virginia, Bragg focused on the defense of areas south and west of Richmond. He convinced Jefferson Davis to appoint P.G.T. Beauregard to an important role in the defense of Richmond and Petersburg. Meanwhile, Davis was concerned that Joseph Johnston, Bragg’s successor at the Army of Tennessee, was defending too timidly against Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. He sent Bragg to Georgia on July 9, charged with investigating the tactical situation, but also evaluating the replacement of Johnston in command. Bragg harbored the hope that he might be chosen to return to command of the army, but was willing to support Davis’s choice. Davis had hinted to Bragg that he thought Hardee would be an appropriate successor, but Bragg was reluctant to promote an old enemy and reported back that Hardee would provide no change in strategy from Johnston’s. Bragg had extensive conversations with a more junior corps commander, Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood, and was impressed with his plans for taking offensive action, about which Hood had also been confidentially corresponding to Richmond for weeks behind Johnston’s back. Davis chose Hood to replace Johnston.[54]

Content retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Braxton_Bragg.