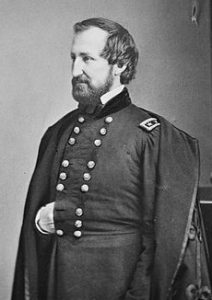

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819 – March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, coal-oil company executive, diplomat, politician, and U.S. Army officer. He gained fame for his role as a Union general during the American Civil War. He was the victor at prominent Western Theater battles, but his military career was effectively ended following his disastrous defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863.

William Starke Rosecrans (September 6, 1819 – March 11, 1898) was an American inventor, coal-oil company executive, diplomat, politician, and U.S. Army officer. He gained fame for his role as a Union general during the American Civil War. He was the victor at prominent Western Theater battles, but his military career was effectively ended following his disastrous defeat at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863.

Rosecrans graduated in 1842 from the United States Military Academy where he served in engineering assignments as well as a professor before leaving the Army to pursue a career in civil engineering. At the start of the Civil War, leading troops from Ohio, he achieved early combat success in western Virginia. In 1862 in the Western Theater, he won the battles of Iuka and Corinth while under the command of Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. His brusque, outspoken manner and willingness to quarrel openly with superiors caused a professional rivalry with Grant (as well as with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton) that would adversely affect Rosecrans’ career.

Given command of the Army of the Cumberland, he fought against Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg at Stones River, and later outmaneuvered him in the brilliant Tullahoma Campaign, driving the Confederates from Middle Tennessee. His strategic movements then caused Bragg to abandon the critical city of Chattanooga, but Rosecrans’ pursuit of Bragg ended during the bloody Battle of Chickamauga, where his unfortunately worded order mistakenly opened a gap in the Union line and Rosecrans and a third of his army were swept from the field. Besieged in Chattanooga, Rosecrans was relieved of command by Grant.

Following his humiliating defeat, Rosecrans was reassigned to command the Department of Missouri, where he opposed Price’s Raid. He was briefly considered as a vice presidential running mate for Abraham Lincoln in 1864 but the telegram correspondence Rosecrans sent back to Washington that stated his interest, was intercepted by Stanton, who buried the message. As a result, Lincoln never received his response and began looking for other candidates. After the war, he served in diplomatic and appointed political positions and in 1880 was elected to Congress, representing California.

American Civil War

Just days after Fort Sumter surrendered, Rosecrans offered his services to Ohio Governor William Dennison, who assigned him as a volunteer aide-de-camp to Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, who commanded all Ohio volunteer forces at the beginning of the war. Promoted to the rank of colonel, Rosecrans briefly commanded the 23rd Ohio Infantry regiment, whose members included Rutherford B. Hayes and William McKinley, both future presidents. He was promoted to brigadier general in the regular army, ranking from May 16, 1861.[10]

His plans and decisions proved extremely effective in the Western Virginia Campaign. His victories at Rich Mountain and Corrick’s Ford in July 1861 were among the very first Union victories of the war, but his superior, Maj. Gen. McClellan, received the credit. Rosecrans then prevented, by “much maneuvering but little fighting,”[12] Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd and his superior, Gen. Robert E. Lee, from recapturing the area that became the state of West Virginia. When McClellan was summoned to Washington after the defeat suffered by Federal forces at the First Battle of Bull Run, General-in-Chief Winfield Scott suggested that McClellan turn over the West Virginia command to Rosecrans. McClellan agreed, and Rosecrans assumed command of what was to become the Department of Western Virginia.[13]

In late 1861, Rosecrans planned for a winter campaign to capture the strategic town of Winchester, Virginia, turning the Confederate flank at Manassas. He traveled to Washington to obtain McClellan’s approval. McClellan disapproved, however, telling Rosecrans that putting 20,000 Union men into Winchester would be countered by Confederates moving an equal number into the vicinity. He also transferred 20,000 of Rosecrans’s 22,000 men to serve under Brig. Gen. Frederick W. Lander, leaving Rosecrans with insufficient resources to do any campaigning. In March 1862, Rosecrans’s department was converted to the Mountain Department, which was given to political general John C. Frémont, leaving Rosecrans without a command. He served briefly in Washington, where his opinions clashed with those of newly appointed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton on tactics and Union command organization for the Shenandoah Valley campaign against Stonewall Jackson. Stanton became one of Rosecrans’s most vocal critics. One of Stanton’s assignments for Rosecrans was to act as a guide for Brig. Gen. Louis Blenker’s division (Frémont’s department) in the valley, and Rosecrans became intimately involved in the political and command confusion in the campaign against Jackson in the Valley.[14]

Chickamauga

Main article: Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga began on September 19 with Bragg attacking the not fully concentrated Union army, but he was unable to break through Rosecrans’s defensive positions. On the second day of battle, however, disaster befell Rosecrans in the form of his poorly worded order in response to a poorly understood situation. The order was directed to Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Wood, “to close up and support [General Joseph J.] Reynolds’s [division],” planning to fill an assumed gap in the line. However, Wood’s subsequent movement actually opened up a new, division-sized gap in the line. By coincidence, a massive assault by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet had been planned to strike that very area and the Confederates exploited the gap to full effect, shattering Rosecrans’s right flank.

The majority of units on the Union right fell back in disorder toward Chattanooga. Rosecrans, Garfield, and two of the corps commanders, although attempting to rally retreating units, soon joined them in the rush to safety. Rosecrans decided to proceed in haste to Chattanooga in order to organize his returning men and the city defenses. He sent Garfield to Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas with orders to take command of the forces remaining at Chickamauga and withdraw.[50]

The Union army managed to escape complete disaster because of the stout defense organized by Thomas on Horseshoe Ridge, heroism that earned him the nickname “Rock of Chickamauga.” The army withdrew that night to fortified positions in Chattanooga. Bragg had not succeeded in his objective to destroy the Army of the Cumberland, but the Battle of Chickamauga was nonetheless the worst Union defeat in the Western Theater. Thomas urged Rosecrans to rejoin the army and lead it, but Rosecrans, physically exhausted and psychologically a beaten man, remained in Chattanooga. President Lincoln attempted to prop up the morale of his general, telegraphing “Be of good cheer. … We have unabated confidence in you and your soldiers and officers. In the main, you must be the judge as to what is to be done. If I was to suggest, I would say save your army by taking strong positions until Burnside joins you.” Privately, Lincoln told John Hay that Rosecrans seemed “confused and stunned like a duck hit on the head.”[51]

Whether he did or did not know that Thomas still held the field, it was a catastrophe that Rosecrans did not himself ride to Thomas, and send Garfield to Chattanooga. Had he gone to the front in person and shown himself to his men, as at Stone River, he might by his personal presence have plucked victory from disaster, although it is doubtful whether he could have done more than Thomas did. Rosecrans, however, rode to Chattanooga instead.

Although Rosecrans’s men were protected by strong defensive positions, the supply lines into Chattanooga were tenuous and subject to Confederate cavalry raids. Bragg’s army occupied the heights surrounding the city and laid siege upon the Union forces. Rosecrans, demoralized by his defeat, proved unable to break the siege without reinforcements. Only hours after the defeat at Chickamauga, Secretary Stanton ordered Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker to travel to Chattanooga with 15,000 men in two corps from the Army of the Potomac in Virginia. Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was ordered to send 20,000 men under his chief subordinate Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, from Vicksburg, Mississippi. On September 29, Stanton ordered Grant to go to Chattanooga himself,[53] as commander of the newly created Military Division of the Mississippi. Grant was given the option of replacing the demoralized Rosecrans with Thomas. Although Grant did not have good personal relations with either general, he selected Thomas to command the Army of the Cumberland. Grant traveled over the treacherous mountain supply line roads and arrived in Chattanooga on October 23.

On the morning of the 21st we took the train for the front, reaching Stevenson Alabama, after dark. Rosecrans was there on his way north. He came into my car and we held a brief interview, in which he described very clearly the situation at Chattanooga, and made some excellent suggestions as to what should be done. My only wonder was that he had not carried them out.

Grant executed a plan originally devised by Rosecrans and Brig. Gen. William F. “Baldy” Smith to open the “Cracker Line” and resupply the army and, in a series of battles for Chattanooga (November 23–25, 1863), routed Bragg’s army and sent it retreating into Georgia.[55]

Missouri and resignation

Rosecrans was sent to Cincinnati to await further orders, but ultimately he would play no further large part in the fighting. He was given command of the Department of Missouri from January to December 1864, when he was active in opposing Sterling Price’s Missouri raid. During the 1864 Republican National Convention, his former chief of staff, James Garfield, head of the Ohio delegation, telegraphed Rosecrans to ask if he would consider running to be Abraham Lincoln’s vice president. The Republicans that year were seeking a War Democrat to run with Lincoln under the temporary name of “National Union Party.” Rosecrans replied in a cryptically positive manner, but Garfield never received the return telegram. Friends of Rosecrans speculated that Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War, intercepted and suppressed it.[56]

Rosecrans was mustered out of the U.S. volunteer service on January 15, 1866. On June 30, 1866, President Andrew Johnson nominated Rosecrans for appointment as a brevet major general in the regular army, to rank from March 13, 1865, in gratitude for his actions at Stones River, and the U.S. Senate confirmed the appointment on July 25, 1866. Rosecrans resigned from the regular army on March 28, 1867. On February 27, 1889, by act of Congress he was re-appointed a brigadier general in the regular army and was placed on the retired list on March 1, 1889.[57]

After the war, Rosecrans became a companion of the District of Columbia Commandery of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States – a military society of officers who had served in the Union armed forces and their descendants.

Content retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Rosecrans.

Images

[URIS id=1221]